Bon Odori (19/7)

Posted on September 7, 2014

Obon (お盆) or just Bon (盆) is a Japanese Buddhist custom to honor the spirits of one’s ancestors. This Buddhist-Confucian custom has evolved into a family reunion holiday during which people return to ancestral family places and visit and clean their ancestors’ graves, and when the spirits of ancestors are supposed to revisit the household altars. It has been celebrated in Japan for more than 500 years and traditionally includes a dance, known as Bon-Odori.

The festival of Obon lasts for three days; however its starting date varies within different regions of Japan. When the lunar calendar was changed to the Gregorian calendar at the beginning of the Meiji era, the localities in Japan reacted differently and this resulted in three different times of Obon. “Shichigatsu Bon” (Bon in July) is based on the solar calendar and is celebrated around 15 July in eastern Japan (Kantō region such as Tokyo, Yokohama and the Tohoku region), coinciding with Chūgen. “Hachigatsu Bon” (Bon in August) is based on the lunar calendar, is celebrated around the 15th of August and is the most commonly celebrated time. “Kyu Bon” (Old Bon) is celebrated on the 15th day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, and so differs each year. “Kyu Bon” is celebrated in areas like the northern part of the Kantō region, Chūgoku region, Shikoku, and the Okinawa Prefecture. These three days are not listed as public holidays but it is customary that people are given leave.

Bon Odori is a Japanese cultural festival which involves traditional and merry-making dance and lively drum performance to welcome the home coming of ancestral spirits. It is traditional belief by the Japanese that the spirits of the deceased ancestors would return once a year to visit their families. And Bon Odori is a traditional Japanese Dance.

The atmosphere at the Esplanade will be fun-filled with stalls selling various types of local and Japanese food, handicrafts and souvenirs, games, firework displays. Traditional Japanese and local cultural danceperformances and music creates a colourful carnival-like and merry atmosphere of a mini ‘Land of the Rising Sun’ at the Esplanade. The ladies will be dressed in casually in stylish summer kimono (Yukata costume) and wearing Japanese wooden clogs (known as geta), while the men are clothed in their short robes complete with shorts or pants and other traditional dressing attires of Japan during Bon Odori festive nite.

» Filed Under Activity report | Leave a Comment

Spring cleaning (16/8)

Posted on August 16, 2014

Spring cleaning is planned annually by the authorities of Kelab Budaya Jepun to make sure the cleanliness of the venue of activities held, that is A3 and A4 class room. Besides, it is also our responsibility to clean the school hall’s side windows.

» Filed Under Activity report | Leave a Comment

Sushi Competition (26/7)

Posted on July 26, 2014

Sushi (すし, 寿司, 鮨) is a Japanese food consisting of cooked vinegared rice (鮨飯 sushi-meshi) combined with other ingredients (ネタneta), seafood, vegetables and sometimes tropical fruits. Ingredients and forms of sushi presentation vary widely, but the ingredient which all sushi have in common is rice (also referred to as shari (しゃり) or sumeshi (酢飯).

Sushi can be prepared with either brown or white rice. Sushi is often prepared with raw seafood, but some common varieties of sushi use cooked ingredients. Raw fish (or occasionally other meat) sliced and served without rice is called “sashimi”.

Sushi is often served with shredded ginger, wasabi, and soy sauce. Popular garnishes are often made using daikon.

Different types of nigiri-zushi and a long, tapered temaki; pickled Gari (ginger) is at the upper right of the serving board

Types of sushi. Clockwise from top-left: nigirizushi, makizushi, temaki.

Types

The common ingredient across all kinds of sushi is vinegared sushi rice. Variety arises from fillings, toppings, condiments, and preparation. Traditional versus contemporary methods of assembly may create very different results from very similar ingredients. In spelling sushi, its first letter s is replaced with z when a prefix is attached, as in nigirizushi, due toconsonant mutation called rendaku in Japanese.

Chirashizushi

Chirashizushi (ちらし寿司, “scattered sushi”) is a bowl of sushi rice topped with a variety of raw fish and vegetables/garnishes (also refers tobarazushi). There is no set formula for the ingredients; they are either chef’s choice or specified by the customer. It is commonly eaten because it is filling, fast and easy to make. Chirashizushi also often varies regionally. It is eaten annually on Hinamatsuri in March.

- Edomae chirashizushi (Edo-style scattered sushi) is served with uncooked ingredients which are arranged artfully on top of the sushi rice in a bowl.

- Gomokuzushi (Kansai-style sushi) consists of cooked or uncooked ingredients mixed in the body of rice in a bowl.

- Sake-zushi (Kyushu-style sushi) is a variety where instead of rice vinegar, rice wine is used in the mixture of the rice, and is topped with shrimp, sea bream, octopus, shiitake mushrooms, bamboo shoots and shredded omelette.

Inarizushi

A version of inarizushi that includes green beans, carrots, and gobo along with rice, wrapped in a triangular aburage (fried tofu) piece, is aHawaiian specialty, where it is called cone sushi and is often sold in okazu-ya (Japanese delis) and as a component of bentoboxes.Inarizushi (稲荷寿司) is a pouch of fried tofu typically filled with sushi rice alone. It is named after the Shinto god Inari, who is believed to have a fondness for fried tofu. The pouch is normally fashioned as deep-fried tofu (油揚げ, abura age). Regional variations include pouches made of a thin omelette (帛紗寿司, fukusa-zushi, or 茶巾寿司, chakin-zushi). It should not be confused with inari maki, which is a roll filled with flavored fried tofu.

Makizushi

Makizushi (巻き寿司, “rolled sushi”), norimaki (海苔巻き, “Nori roll”) or makimono (巻物, “variety of rolls”) is a cylindrical piece, formed with the help of a bamboo mat known as a makisu (巻簾). Makizushi is generally wrapped in nori (seaweed), but is occasionally wrapped in a thinomelette, soy paper, cucumber, or shiso (perilla) leaves. Makizushi is usually cut into six or eight pieces, which constitutes a single roll order. Below are some common types of makizushi, but many other kinds exist.

Futomaki (太巻, “thick, large or fat rolls”) is a large cylindrical piece, usually with nori on the outside. A typical futomaki is five to six centimeters (2–2.5 in) in diameter. They are often made with two, three, or more fillings that are chosen for their complementary tastes and colors. During the evening of the Setsubun festival, it is traditional in the Kansai region to eat uncut futomaki in its cylindrical form, where it is called ehō-maki (恵方巻, lit. happy direction rolls). By 2000 the custom had spread to all of Japan. Futomaki are often vegetarian, and may utilize strips of cucumber, kampyō gourd, takenoko bamboo shoots, or lotus root. Strips of tamagoyaki omelette, tiny fish roe, chopped tuna, and oboro whitefish flakes are typical non-vegetarian fillings.

Hosomaki (細巻, “thin rolls”) is a small cylindrical piece, with nori on the outside. A typical hosomaki has a diameter of about two and a half centimeters (1 in). They generally contain only one filling, often tuna, cucumber, kanpyō, thinly sliced carrots, or, more recently, avocado.Kappamaki, (河童巻) a kind of Hosomaki filled with cucumber, is named after the Japanese legendary water imp fond of cucumbers called thekappa. Traditionally, kappamaki is consumed to clear the palate between eating raw fish and other kinds of food, so that the flavors of the fish are distinct from the tastes of other foods. Tekkamaki (鉄火巻) is a kind of hosomaki filled with raw tuna. Although it is believed that the wordtekka, meaning “red hot iron”, alludes to the color of the tuna flesh or salmon flesh, it actually originated as a quick snack to eat in gambling dens called tekkaba (鉄火場), much like the sandwich.[19][20] Negitoromaki (ねぎとろ巻) is a kind of hosomaki filled with scallion (negi) and chopped tuna (toro). Fatty tuna is often used in this style. Tsunamayomaki (ツナマヨ巻) is a kind of hosomaki filled with canned tuna tossed with mayonnaise.

Temaki (手巻, “hand roll”) is a large cone-shaped piece of nori on the outside and the ingredients spilling out the wide end. A typical temaki is about ten centimeters (4 in) long, and is eaten with fingers because it is too awkward to pick it up with chopsticks. For optimal taste and texture, temaki must be eaten quickly after being made because the nori cone soon absorbs moisture from the filling and loses its crispness, making it somewhat difficult to bite through. For this reason, the nori in pre-made or take-out temaki is sealed in plastic film which is removed immediately before eating.

Narezushi

Narezushi (熟れ寿司, “matured sushi”) is a traditional form of fermented sushi. Skinned and gutted fish are stuffed with salt, placed in a wooden barrel, doused with salt again, then weighed down with a heavy tsukemonoishi (pickling stone). As days pass, water seeps out and is removed. After six months, this sushi can be eaten, remaining edible for another six months or more. The most famous variety of narezushi still being produced is funa-zushi (made from fish of the crucian carp genus, authentically from C. auratus grandoculis (nigoro-buna) endemic to Lake Biwa), a typical dish of Shiga Prefecture.

Nigirizushi

Nigirizushi (握り寿司, “hand-pressed sushi”) consists of an oblong mound of sushi rice that the chef presses into a small rectangular box between the palms of the hands, usually with a bit of wasabi, and a topping (the neta) draped over it. Neta are typically fish such as salmon, tuna or other seafood. Certain toppings are typically bound to the rice with a thin strip of nori, most commonly octopus (tako), freshwater eel (unagi), sea eel (anago), squid(ika), and sweet egg (tamago). One order of a given type of fish typically results in two pieces, while a sushi set (sampler dish) may contain only one piece of each topping.

Gunkanmaki (軍艦巻, “warship roll”) is a special type of nigirizushi: an oval, hand-formed clump of sushi rice that has a strip of nori wrapped around its perimeter to form a vessel that is filled with some soft, loose or fine-chopped ingredient that requires the confinement of nori such as roe, nattō, oysters,uni (sea urchin roe), corn with mayonnaise, scallops, and quail eggs. Gunkan-maki was invented at the Ginza Kyubey restaurant in 1941; its invention significantly expanded the repertoire of soft toppings used in sushi.

Temarizushi (手まり寿司, “ball sushi”) is a ball-shaped sushi made by pressing rice and fish into a ball-shaped form by hand using a plastic wrap.

Oshizushi

Oshizushi (押し寿司, “pressed sushi”), also known as 箱寿司, hako-zushi, “box sushi”), is a pressed sushi from the Kansai region, a favorite and specialty of Osaka. A block-shaped piece formed using a wooden mold, called an oshibako. The chef lines the bottom of the oshibako with the toppings, covers them with sushi rice, and then presses the lid of the mold down to create a compact, rectilinear block. The block is removed from the mold and then cut into bite-sized pieces. Particularly famous is バッテラ (battera, pressed mackerel sushi) or 鯖寿司 (saba zushi).

» Filed Under Activity report | Leave a Comment

Yukata Wearing (19/4)

Posted on April 19, 2014

The yukata (浴衣) is a casual version of the kimono. It is a robe usually made of cotton or synthetic fabric, wrapped around the body and fastened with a sash (obi). Yukata literally means “bathing cloth”, and it was originally intended to be just that. Traditionally, the garment is worn after bathing in a communal bath, functioning as a quick way to cover the body and to absorb remaining moisture.

Recently, the yukata has also become a way of dressing for summer festivals. Increasingly fashionable designs have surfaced to a degree that it is sometimes difficult for the untrained eye to discern between a yukata and a kimono. Yukata for men generally have darker or more subdued colors, while that for young women are usually bright and colorful, often with floral designs. Yukata for matured women tend to be less flashy.

Your yukata set, which consists of a yukata, an obi (belt) and sometimes socks. Some ryokan may only have one size of yukata available, although more often they offer a selection of sizes either in your room or provided by your attendant. If given a choice of sizes, choose one that rests just at the ankle.

How to dress in Yukata

Step 1: Put on your yukata over your underwear (undershirt and socks are optional). Slip your arms into the sleeves of the yukata and grasp it along its front hem, one side in each hand, at about waist level. Fold the right hand side underneath the left hand side, and hold it in place with your hand.

Step 2: Now fold the left hand over the right hand side and hold it in place with your hand while you get your obi (belt).

men |

women |

Step 3: Secure everything in place with the obi (belt) by wrapping it around your waist. Begin in the front and wrap it around your back. The obi are usually stored folded into little pentagons, so look for these if you are having trouble finding the obi.

Step 4: Cross the belt around your back and tie it in the front. For men, the belt should rest fairly low on the hips. For women, the belt is tied at the waist.

men |

women |

Step 5: Adjust the length of the belt ends so that they hang evenly from your right hip. Then adjust the knot so that it lies on your right hip.

men |

women |

Members are divided into groups of 3 or 4. This is because it’s difficult to dress alone. While steps are shown before the wearing session starts. Photos of member wearing Yukata:

- Members taking photos after wearing yukata.

- Members wearing Yukata and posed for photograph session.

- Members posed for photograph session.

- Members posed for photograph session.

- Teaching how to wear yukata before wearing session.

» Filed Under Activity report | Leave a Comment

Yukata Wearing (12/4)

Posted on April 12, 2014

How To Wear A Yukata?

When you are in Japan, you might consider buying a yukata (cotton summer kimono) or, if you have the money for it, an actual kimono. Mind you, real silk hand painted kimono’s are not exactly cheap so bring your creditcard if you are keen on getting one! Still it is one size fits all so compared to western style clothes it is a much better investment, although you might not have that many opportunities to wear them.

Once you have purchased your kimono or yukata, now comes the question… how to wear this beautiful piece of garment?

How to wear a yukata, step by step:

1. Put the Yukata on. Flip the long sleeves back over your arms, so that they won’t be in your way. 2. While one hand is holding both sides of the fabric together in front of your body, try to locate the center line of the garment (where the fabrics are sewed together)on the back of your body using the other hand. Fix the garment to the center. 3. Open up the garment and pull it up to the ankle level. 4. Bring the left side of the garment to the front and decide the correct length and width. 5. Open up the left side while keeping the length and bring the right side to the front. Decide the length. Bottom corner of the right side of the garment should be about 4″ from the ground. 6. Keep the right side garment and bring the left side on top of it. Decide the length. The bottom corner of the left side garment should be about 2″ from the ground. 7. Use Koshi-Himo and tie the garment around the waist. Make sure to tie tightly to avoid the garment getting loose. Tuck the Koshi-Himo in. 8. Find the side pockets, stick both hands, and pull the extra fabric over Koshi-Himo. Make sure to do the front and the back. *This layer around the waist is called Ohashori. Ohashori is supposed to show below the Obi. 9. Fix the shape of Ohashori and tie the second Koshi-Himo right below the bust. This one does not have to be as tight as the first one. Tuck the Koshi-Himo ends in. 10. If you are slim build, you may have extra fabric on the side of the upper body. At the side pockets, pull the back fabric to the front and the pull back the front fabric over it to hide the extra fabric. This will make a clean side look. 11. And now you are done! Make sure to tie an Obi around the waist for the complete Yukata look.

» Filed Under Activity report | Leave a Comment

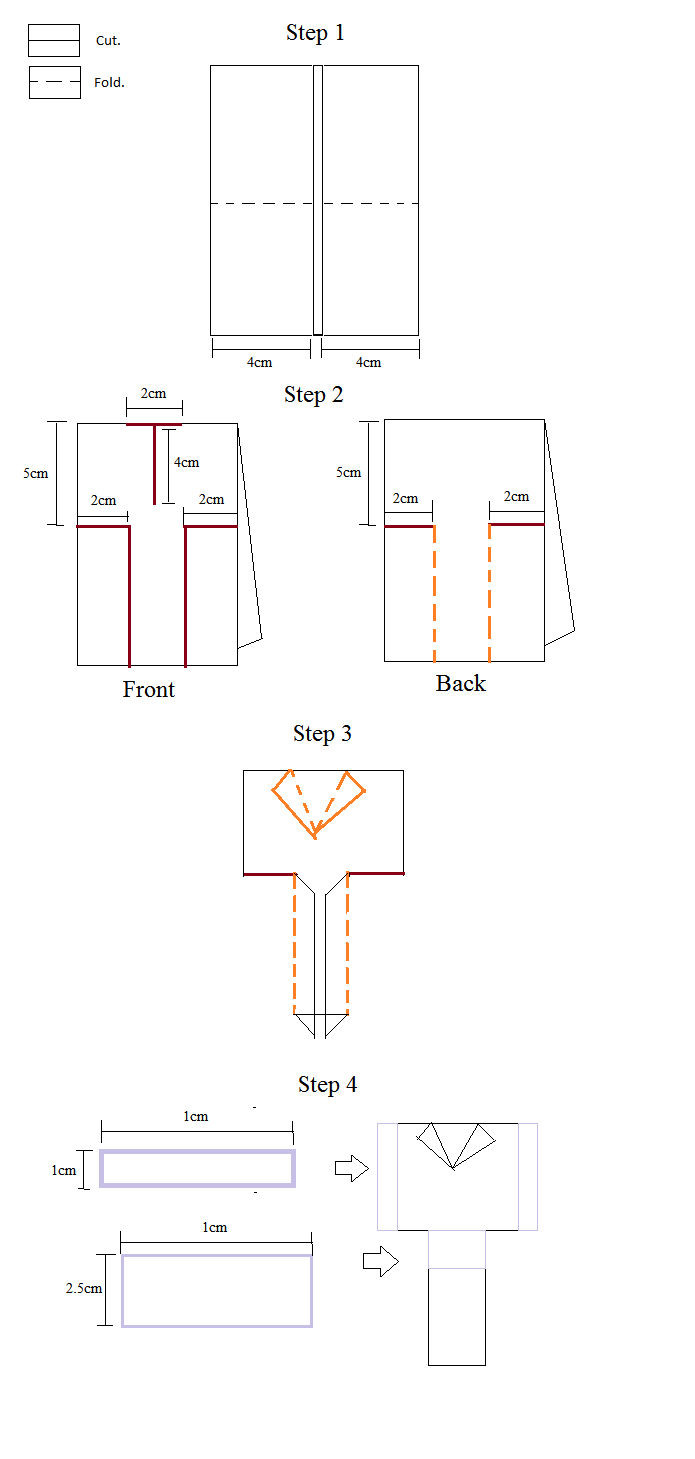

Making of Kimono Bookmark (22/3)

Posted on March 22, 2014

Feeling annoyed when you can’t find the page that u read last? No problem, just make a bookmark! Try out the Kimono Bookmark~

Just a few steps and you Kimono Bookmark is prepared!!!

Steps

1) Print the pattern that you like in A4 size.

2) After measuring everything, cut out the part that needed carefully.

3) Fold the piece into half.

4) Measure and then cut it.

5) Next, fold the 2 side part inwards.While the colar part is folded outwards.

6) Cut out 2 strips of 1cm x 1cm and 1 strips of 2.5cm x 1cm.

7) Covered the sleeve part with the 1cm x 1 cm striips each side.

8) Covered the waist part with 2.5cm x 1cm strips.

9) Decorate it.

10) Cut a 2cm x 11cm card.

11) Write down some quotes u like.

12)Punch a hole and tie with a ribbon.

13) Slide it in between the colar.

14) Kimono bookmark is done!

» Filed Under Activity report | Leave a Comment

Origami (8/2)

Posted on February 8, 2014

Origami (折り紙, from ori meaning “folding”, and kami meaning “paper” (kami changes to gami due to rendaku) is the traditional Japanese art of paper folding, which started in the 17th century AD at the latest and was popularized outside of Japan in the mid-1900s. It has since evolved into a modern art form. The goal of this art is to transform a flat sheet of paper into a finished sculpture through folding and sculpting techniques, and as such the use of cuts or glue are not considered to be origami. Paper cutting and gluing is usually considered kirigami.

The number of basic origami folds is small, but they can be combined in a variety of ways to make intricate designs. The best known origami model is probably the Japanese paper crane. In general, these designs begin with a square sheet of paper whose sides may be different colors or prints. Traditional Japanese origami, which has been practiced since the Edo era (1603–1867), has often been less strict about these conventions, sometimes cutting the paper or using nonsquare shapes to start with.

The principles of origami are also used in stents, packaging and other engineering structures.

History

There is much speculation about the origin of Origami. While Japan seems to have had the most extensive tradition, there is evidence of an independent tradition of paperfolding in China, as well as in Germany, Italy and Spain, among other places. However, because of the problems associated with preserving origami, there is very little direct evidence of its age or origins, aside from references in published material.

In China, traditional funerals include burning folded paper, most often representations of gold nuggets (yuanbao). It is not clear when this practice actually started, but it seems to have become popular during the Sung Dynasty (905–1125 CE). The paper folding has typically been of objects like dishes, hats or boats rather than animals or flowers.

The earliest evidence of paperfolding in Europe is a picture of a small paper boat in Tractatus de sphaera mundi, a textbook on astronomy, from 1490. There is also evidence of a cut and folded paper box from 1440. It is probable that paperfolding in the west originated with theMoors much earlier; it is not known if it was independently discovered or knowledge of origami came along the silk route.

In Japan, the earliest unambiguous reference to a paper model is in a short poem by Ihara Saikaku in 1680 which describes paper butterflies in a dream. Origami butterflies were used during the celebration of Shinto weddings to represent the bride and groom, so paperfolding had already become a significant aspect of Japanese ceremony by the Heian period (794–1185) of Japanese history, enough that the reference in this poem would be recognized. Samurai warriors would exchange gifts adorned with noshi, a sort of good luck token made of folded strips of paper.

In the early 1900s, Akira Yoshizawa, Kosho Uchiyama, and others began creating and recording original origami works. Akira Yoshizawa in particular was responsible for a number of innovations, such as wet-folding and the Yoshizawa–Randlett diagramming system, and his work inspired a renaissance of the art form. During the 1980s a number of folders started systematically studying the mathematical properties of folded forms, which led to a steady increase in the complexity of origami models, which continued well into the 1990s, after which some designers started returning to simpler forms

Techniques and materials

Techniques

Many origami books begin with a description of basic origami techniques which are used to construct the models. This includes simple diagrams of basic folds like valley and mountain folds, pleats, reverse folds, squash folds, and sinks. There are also standard named bases which are used in a wide variety of models, for instance the bird base is an intermediate stage in the construction of the flapping bird.Additional bases are the preliminary base (square base), fish base, waterbomb base, and the frog base.

Origami paper

Almost any laminar (flat) material can be used for folding; the only requirement is that it should hold a crease.

Origami paper, often referred to as “kami” (Japanese for paper), is sold in prepackaged squares of various sizes ranging from 2.5 cm (1 in) to 25 cm (10 in) or more. It is commonly colored on one side and white on the other; however, dual coloured and patterned versions exist and can be used effectively for color-changed models. Origami paper weighs slightly less than copy paper, making it suitable for a wider range of models.

Normal copy paper with weights of 70–90 g/m2 can be used for simple folds, such as the crane and waterbomb. Heavier weight papers of (19–24&nb 100 g/m2 (approx. 25 lb) or more can be wet-folded. This technique allows for a more rounded sculpting of the model, which becomes rigid and sturdy when it is dry.

Foil-backed paper, as its name implies, is a sheet of thin foil glued to a sheet of thin paper. Related to this is tissue foil, which is made by gluing a thin piece of tissue paper to kitchen aluminium foil. A second piece of tissue can be glued onto the reverse side to produce a tissue/foil/tissue sandwich. Foil-backed paper is available commercially, but not tissue foil; it must be handmade. Both types of foil materials are suitable for complex models.

Washi (和紙) is the traditional origami paper used in Japan. Washi is generally tougher than ordinary paper made from wood pulp, and is used in many traditional arts. Washi is commonly made using fibres from the bark of the gampi tree, the mitsumata shrub (Edgeworthia papyrifera), or thepaper mulberry but can also be made using bamboo, hemp, rice, and wheat.

Artisan papers such as unryu, lokta, hanji , gampi, kozo, saa, and abaca have long fibers and are often extremely strong. As these papers are floppy to start with, they are often backcoated or resized with methylcellulose or wheat paste before folding. Also, these papers are extremely thin and compressible, allowing for thin, narrowed limbs as in the case of insect models.

Paper money from various countries is also popular to create origami with; this is known variously as Dollar Origami, Orikane, and Money Origami.

Tools

Bone folders

It is common to fold using a flat surface, but some folders like doing it in the air with no tools, especially when displaying the folding. Many folders believe that no tool should be used when folding. However a couple of tools can help especially with the more complex models. For instance a bone folder allows sharp creases to be made in the paper easily, paper clips can act as extra pairs of fingers, and tweezers can be used to make small folds. When making complex models from origami crease patterns, it can help to use a ruler and ballpoint embosser to score the creases. Completed models can be sprayed so they keep their shape better, and a spray is needed when wet folding.

Types of origami

Action origami

Origami not only covers still-life, there are also moving objects; Origami can move in clever ways. Action origami includes origami that flies, requires inflation to complete, or, when complete, uses the kinetic energy of a person’s hands, applied at a certain region on the model, to move another flap or limb. Some argue that, strictly speaking, only the latter is really “recognized” as action origami. Action origami, first appearing with the traditional Japanese flapping bird, is quite common. One example is Robert Lang’s instrumentalists; when the figures’ heads are pulled away from their bodies, their hands will move, resembling the playing of music.

Modular origami

Modular origami consists of putting a number of identical pieces together to form a complete model. Normally the individual pieces are simple but the final assembly may be tricky. Many of the modular origami models are decorative balls like kusudama, the technique differs though in that kusudama allows the pieces to be put together using thread or glue.

Chinese paper folding includes a style called Golden Venture Folding where large numbers of pieces are put together to make elaborate models. It is most commonly known as “3d origami”, however, that name did not appear until Joie Staff published a series of books titled “3D Origami”, “More 3D Origami”, and “More and More 3D Origami”. Sometimes paper money is used for the modules. This style originated from some Chinese refugees while they were detained in America and is also called Golden Venture folding from the ship they came on.

Wet-folding

Wet-folding is an origami technique for producing models with gentle curves rather than geometric straight folds and flat surfaces. The paper is dampened so it can be moulded easily, the final model keeps its shape when it dries. It can be used, for instance, to produce very natural looking animal models. Size, an adhesive that is crisp and hard when dry, but dissolves in water when wet and becoming soft and flexible, is often applied to the paper either at the pulp stage while the paper is being formed, or on the surface of a ready sheet of paper. The latter method is called external sizing and most commonly uses Methylcellulose, or MC, paste, or various plant starches.

Pureland origami

Pureland origami is origami with the restriction that only one fold may be done at a time, more complex folds like reverse folds are not allowed, and all folds have straightforward locations. It was developed by John Smith in the 1970s to help inexperienced folders or those with limited motor skills. Some designers also like the challenge of creating good models within the very strict constraints.

Origami tessellations

This branch of origami is one that has grown in popularity recently. A tessellation is a collection of figures filling a plane with no gaps or overlaps. In origami tessellations, pleats are used to connect molecules such as twist folds together in a repeating fashion.

During the 1960s, Shuzo Fujimoto was the first to explore twist fold tessellations in any systematic way, coming up with dozens of patterns and establishing the genre in the origami mainstream. Around the same time period, Ron Resch patented some tessellation patterns as part of his explorations into kinetic sculpture and developable surfaces, although his work was not known by the origami community until the 1980s. Chris Palmer is an artist who has extensively explored tessellations after seeing the Zilij patterns in the Alhambra, and has found ways to create detailed origami tessellations out of silk. Robert Lang and Alex Bateman are two designers who use computer programs to create origami tessellations.

Kirigami

Kirigami is a Japanese term for paper cutting. Cutting was often used in traditional Japanese origami, but modern innovations in technique have made the use of cuts unnecessary. Most origami designers no longer consider models with cuts to be origami, instead using the term Kirigami to describe them. This change in attitude occurred during the 1960s and 70s, so early origami books often use cuts, but for the most part they have disappeared from the modern origami repertoire; most modern books don’t even mention cutting.

Mathematics and technical origami

Mathematics and practical applications

The practice and study of origami encapsulates several subjects of mathematical interest. For instance, the problem of flat-foldability (whether a crease pattern can be folded into a 2-dimensional model) has been a topic of considerable mathematical study.

A number of technological advances have come from insights obtained through paper folding. For example, techniques have been developed for the deployment of car airbags and stent implants from a folded position.

The problem of rigid origami (“if we replaced the paper with sheet metal and had hinges in place of the crease lines, could we still fold the model?”) has great practical importance. For example, the Miura map fold is a rigid fold that has been used to deploy large solar panel arrays for space satellites.

Origami can be used to construct various geometrical designs not possible with compass and straightedge constructions. For instance paper folding may be used for angle trisection and doubling the cube.

There are plans for an origami airplane to be launched from space. A prototype passed a durability test in a wind tunnel on March 2008, and Japan’s space agency adopted it for feasibility studies.

Technical origami

Technical origami, also known as origami sekkei (折り紙設計), is a field of origami that has developed almost hand-in-hand with the field of mathematical origami. In the early days of origami, development of new designs was largely a mix of trial-and-error, luck and serendipity. With advances in origami mathematics however, the basic structure of a new origami model can be theoretically plotted out on paper before any actual folding even occurs. This method of origami design was developed by Robert Lang, Meguro Toshiyuki and others, and allows for the creation of extremely complex multi-limbed models such as many-legged centipedes, human figures with a full complement of fingers and toes, and the like.

The main starting point for such technical designs is the crease pattern (often abbreviated as CP), which is essentially the layout of the creases required to form the final model. Although not intended as a substitute for diagrams, folding from crease patterns is starting to gain in popularity, partly because of the challenge of being able to ‘crack’ the pattern, and also partly because the crease pattern is often the only resource available to fold a given model, should the designer choose not to produce diagrams. Still, there are many cases in which designers wish to sequence the steps of their models but lack the means to design clear diagrams. Such origamists occasionally resort to the sequenced crease pattern (SCP) which is a set of crease patterns showing the creases up to each respective fold. The SCP eliminates the need for diagramming programs or artistic ability while maintaining the step-by-step process for other folders to see. Another name for the sequenced crease pattern is the progressive crease pattern (PCP).

Paradoxically enough, when origami designers come up with a crease pattern for a new design, the majority of the smaller creases are relatively unimportant and added only towards the completion of the crease pattern. What is more important is the allocation of regions of the paper and how these are mapped to the structure of the object being designed. For a specific class of origami bases known as ‘uniaxial bases’, the pattern of allocations is referred to as the ‘circle-packing’. Using optimization algorithms, a circle-packing figure can be computed for any uniaxial base of arbitrary complexity. Once this figure is computed, the creases which are then used to obtain the base structure can be added. This is not a unique mathematical process, hence it is possible for two designs to have the same circle-packing, and yet different crease pattern structures.

As a circle encloses the maximum amount of area for a given perimeter, circle packing allows for maximum efficiency in terms of paper usage. However, other polygonal shapes can be used to solve the packing problem as well. The use of polygonal shapes other than circles is often motivated by the desire to find easily locatable creases (such as multiples of 22.5 degrees) and hence an easier folding sequence as well. One popular offshoot of the circle packing method is box-pleating, where squares are used instead of circles. As a result, the crease pattern that arises from this method contains only 45 and 90 degree angles, which makes for easier folding.

A number of computer aids to origami such as TreeMaker and Oripa, have been devised. Treemaker allows new origami bases to be designed for special purposes and Oripa tries to calculate the folded shape from the crease pattern.

Ethics

Copyright in origami designs and the use of models has become an increasingly important issue as the internet has made the sale and distribution of pirated designs very easy. It is considered good ethics to always credit the original artist and the folder when displaying origami models. All commercial rights to designs and models are typically reserved by origami artists. Normally a person who folds a model using a legally obtained design can publicly display the model unless such rights are specifically reserved, however folding a design for money or commercial use of a photo for instance would require consent. It can be difficult to contact individual designers for permission or payment therefore there is a drive to set up a group to ease such issues.

Gallery

These pictures show examples of various types of origami.

» Filed Under Activity report | Leave a Comment

AGM Kelab Budaya Jepun 2014 (11/1)

Posted on January 11, 2014

Date : 11 January 2014

Time : 11.30am – 12.30pm

Venue : A4 classroom

Japanese Culture Society AJK List 2014

President : Sim Yee Shan (S5D)

Vice president : Melissa Wong (S4E)

Lim Ruo Xuen (S5D)

Secretary : Tan Rou Jing (S5B)

Vice Secretary : Khor Kai Wern (K3I)

Treasurer : Cheah Zi Hooi (S5C)

Vice secretary : Heng Wan Jing (K3D)

Cleanliness : Lui Qiao Ying (K3D)

Stock-in-charge : Ong Wei Ming (S5C)

Form Representatives : F1-Joslyn Yeoh Ker Xin (K1I)

F2-Hor Mei Xue (K2D)

F3-Teoh Wei Xin (K3A)

F4-Chuah Kai Wei (S4C)

F5-Estee Khoo (S5E)

Ajk : Wong Wei Xuan (K2D)

» Filed Under AGM | Leave a Comment

About

Posted on February 6, 2013

This is an example of an iSchool-Blog page, you could edit this to put information about yourself or your site so readers know where you are coming from. You can create as many pages like this one or sub-pages as you like and manage all of your content inside of iSchool-Blog.

» Filed Under Extra Info | Leave a Comment